The Massachusetts Bay colony launched its first sea-going vessel in 1631. By 1638 the first American shipyard had been established near Portland, Maine, employing 60 men. Along the Atlantic seaboard, the ocean and its tributaries quickly became highways of commerce for a fledgling country. Although dependent upon a triangular trade with England before the Revolution, trade acts and wars soon focused America’s attention elsewhere.

The year after the 1783 Treaty of Paris confirmed the United States’ independence, the New York merchant ship EMPRESS OF CHINA crossed the Atlantic and rounded the Cape of Good Hope, bound for Macao and Canton to open up the fabulously profitable China trade. Five years later, 15 American vessels called at Canton on a single day. During the same period “Yankee Mariners” visited Baltic, Mediterranean, and African ports, and traded with West India, Sumatra, and India.

The upstart American merchant marine flourished even in the face of competition with the established maritime powers. In 1789, the new United States had 124,000 deadweight tons of shipping in its fleet. By 1800, despite French, British, and Algerian despoliation’s, the aggregate American tonnage was more than 667,100 tons. Ten years later, nearly one million tons of shipping sailed under the American flag, bound for ports in every corner of the globe.

This valuable and growing trade had to be protected. Attacks by Barbary pirates as well as French and British warships and privateers — armed merchantmen — resulted in a loss of some 600 ships and about $20 million before Congress, finally outraged, in 1800 raised the first U.S. Navy under the federal Constitution. In this early period of our history, the American merchant marine was a formidable “auxiliary” that at times outperformed its commissioned Navy counterparts. Privateers were a critical element of U.S. sea power in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. In 1776, the colonies had only 31 public ships, and only one of these actually survived the Revolution. Five years later the Americans had 449 privateers mounting 6,735 guns. These armed merchant vessels were responsible for three-quarters of the 800 British vessels, valued at $24 million as prizes of war that were captured during the first two years of the conflict. During the War of 1812, 515 U.S. privateers took 1,345 British ships.

There was legislative protection as well. One of the initial acts of the first session of the first Congress under the new federal Constitution of 1789 was a bill to impose a tariff on imports. Two laws of 1789 applied lower duties on imports carried on American vessels and levied higher tonnage and port charges against foreign ships. Later, the Navigation Act of 1817 forbade the importation of goods from any foreign port except in U.S. vessels or vessels of the country from which the goods were imported. As a result, in 1826, U.S.-flag merchant vessels carried 92.5 percent of America’s foreign trade. More importantly, the 1817 Act completely excluded foreign vessels from the U.S. coastal trade, or cabotage. Both elements were reactions to similar and sometimes more far-reaching prohibitions imposed by most of America’s trading partners.

The Shipping Act of 1916 hurriedly put in place a mechanism to build desperately needed ships, but the Great War ended before most could be delivered. In early 1917, only 61 shipyards — 24 of them capable of building wooden vessels only — operated in the United States. A year later, with promises of $3 billion in government ship orders, 341 shipyards boasted 1,284 launching ways. Production ultimately quadrupled pre-war rates, but nearly one-third of the ships built under the 1916 Act were begun after the Armistice was announced. Throughout the next decade, ships that had cost as much as $400 per ton to build were sold for as low as $14 per ton.

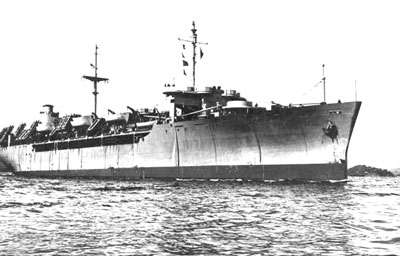

The Shipping Act of 1916 hurriedly put in place a mechanism to build desperately needed ships, but the Great War ended before most could be delivered. In early 1917, only 61 shipyards — 24 of them capable of building wooden vessels only — operated in the United States. A year later, with promises of $3 billion in government ship orders, 341 shipyards boasted 1,284 launching ways. Production ultimately quadrupled pre-war rates, but nearly one-third of the ships built under the 1916 Act were begun after the Armistice was announced. Throughout the next decade, ships that had cost as much as $400 per ton to build were sold for as low as $14 per ton. The early months of World War II were “déjà vu all over again.” Losing 519 ships in the first 180 days of hostilities, the United States was proven once more to be ill-prepared for war. An emergency shipbuilding program was hastily organized, and eventually more than four million Americans were building ships for victory. By September 1945, some 5,000 cargo and troop ships — and more than 1,500 warships — had been built. One historian recounted that the “invasion of Normandy in June 1944 alone had kept 1.5 million tons of shipping busy.” Estimates of World War II logistics concluded that six tons of cargo space per man were required for establishing beachheads and thereafter one ton per man per month was required for maintenance.

The early months of World War II were “déjà vu all over again.” Losing 519 ships in the first 180 days of hostilities, the United States was proven once more to be ill-prepared for war. An emergency shipbuilding program was hastily organized, and eventually more than four million Americans were building ships for victory. By September 1945, some 5,000 cargo and troop ships — and more than 1,500 warships — had been built. One historian recounted that the “invasion of Normandy in June 1944 alone had kept 1.5 million tons of shipping busy.” Estimates of World War II logistics concluded that six tons of cargo space per man were required for establishing beachheads and thereafter one ton per man per month was required for maintenance.

The Gulf War identified numerous valuable lessons and exposed glaring deficiencies. Vice Admiral Paul Butcher, then-Deputy Commander of the U.S. Transportation Command, in mid-February 1991 remarked that this time the United States enjoyed “the best seaports, the best airports…. If you take away any of those equations, you’ve got a hell of a mess and the shortfalls in airlift and sealift would have been exposed.” Without the availability of foreign-flag sealift, moreover, Butcher concluded that “It would have taken us three more months to complete the sealift ourselves.”

The Gulf War identified numerous valuable lessons and exposed glaring deficiencies. Vice Admiral Paul Butcher, then-Deputy Commander of the U.S. Transportation Command, in mid-February 1991 remarked that this time the United States enjoyed “the best seaports, the best airports…. If you take away any of those equations, you’ve got a hell of a mess and the shortfalls in airlift and sealift would have been exposed.” Without the availability of foreign-flag sealift, moreover, Butcher concluded that “It would have taken us three more months to complete the sealift ourselves.”